Monday 19 November 2012

Monday 12 November 2012

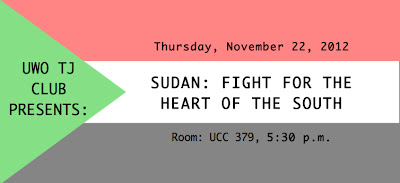

Exciting Upcoming Term 1 Events!

Hello TJ Club members!!!

We are excited to announce two exclusive TJ Club events that

will be taking place before the end of this term!

1) Sudan: Lokuju Silfo is currently a student at Huron College here at Western. He will be sharing about his experience as a refugee from South Sudan. We will watch a short documentary together before we launch into an informal question and answer period with Lokuju. A unique opportunity to engage in valuable student-to-student dialogue and to gain insight into a first hand post-conflict experience of particular relevance given Sudan's recent North/South divide.

1) Sudan: Lokuju Silfo is currently a student at Huron College here at Western. He will be sharing about his experience as a refugee from South Sudan. We will watch a short documentary together before we launch into an informal question and answer period with Lokuju. A unique opportunity to engage in valuable student-to-student dialogue and to gain insight into a first hand post-conflict experience of particular relevance given Sudan's recent North/South divide.

When? Thursday, November 22nd, 2012 @ 5:30

p.m.

Where? TBA (Keep an eye out for an email from us about this! We're waiting on a room confirmation from USC.)

2) Canada: Representatives from Atlohsa, a London-based

First Nations organization that seeks to provide support,

understanding, education, intervention and prevention to victims of family

violence, will be coming to talk to the TJ Club about the Canadian Truth and

Reconciliation Commission! We will listen to an interactive presentation by the

very knowledgeable Atlohsa reps, and launch into a discussion of questions such

as:

What is the TRC?

What are the states goals of the TRC and has the TRC met/is it on its way to meeting those goals?

How does the TRC balance truth and reconciliation?

How does the commission receive stories and is there ample opportunity for community members to have their stories heard?

What can be done to improve upon the TRC process? Do you recommend some other system other than the TRC that might be more effective in this type of role?

What is the TRC?

What are the states goals of the TRC and has the TRC met/is it on its way to meeting those goals?

How does the TRC balance truth and reconciliation?

How does the commission receive stories and is there ample opportunity for community members to have their stories heard?

What can be done to improve upon the TRC process? Do you recommend some other system other than the TRC that might be more effective in this type of role?

When: Thursday, December 6th, 2012 @ 6:00 p.m.

Where? TBA (Again, keep an eye out for an email re: room

location!)

Spread the word/bring friends!

THERE WILL BE SNACKS! :)

Sunday 14 October 2012

Decision in Mau Mau Case Strengthens the Right to Reparations of All Victims of Torture

10/5/2012

The

International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) strongly welcomes

the decision of the UK High Court ordering the British government to pay

damages to a group of Kenyans who were imprisoned and tortured by

colonial authorities following the Mau Mau Rebellion of the 1950s.

“The UK has the opportunity to set right an old injustice, as well as the possibility of strengthening the right to remedy and reparations that continue to be relevant in the present,” said David Tolbert, president of ICTJ. “The British Government should embrace the opportunity to make meaningful reparations not only to the individual claimants but to the hundreds of other surviving victims who are also likely to seek damages before the courts.”

“The UK has the opportunity to set right an old injustice, as well as the possibility of strengthening the right to remedy and reparations that continue to be relevant in the present,” said David Tolbert, president of ICTJ. “The British Government should embrace the opportunity to make meaningful reparations not only to the individual claimants but to the hundreds of other surviving victims who are also likely to seek damages before the courts.”

The lawyers representing the UK government accepted that the three plaintiffs were tortured by the colonial authorities. While imprisoned, they suffered what their lawyers described as "unspeakable acts of brutality," including castration, beatings, and severe sexual assaults.

“Any settlement with the victims in this case should focus on the recognition of the individual and collective suffering inflicted upon Mau Mau veterans, including those who have passed away,” said Ruben Carranza, director of ICTJ’s Reparative Justice Program.

|

| Photo: Oxfam Italia |

In a 2010 ICTJ report, “To Live as Other Kenyans Do,” the interviewed veterans of the Mau Mau insurgency felt that their story had “never been told,” and sought to ensure that their experiences were recorded before it was too late for the old people involved.

They pointed out that “not only has the Mau Mau story not been told, but the organization remained formally illegal until 2003. While veterans also seek support to counter the poverty experienced by many Kenyan victims of other periods, seeing their story told in Kenya’s schools is a priority, as is seeing the heroes of that resistance celebrated. The first ’Heroes’ Day’ in 2010 was a start, but it remains insufficient for those who fought.”

Source: http://ictj.org/news/decision-mau-mau-case-strengthens-right-reparations-all-victims-torture

Thursday 27 September 2012

ICTJ to Brief UN Security Council on Accountability for Crimes Against Children

New York, NY- Accountability for violations against

children in armed conflict is best achieved through a comprehensive

approach to justice that addresses the responsibility of perpetrators

and the rights of victims within a broader process of social change.

This is the key message to be delivered by the International Center for

Transitional Justice (ICTJ) on September 19, 2012, during the UN

Security Council’s Open Debate on Children and Armed Conflict.

“Prosecutions are essential for accountability, as they send a clear message that certain violations will not be tolerated by the society or the international community. However, ICTJ’s work over the past decade in over 40 countries has shown that in isolation, prosecutions are not enough,” said David Tolbert, president of ICTJ.

In his address to the Security Council, Tolbert will recommend that the full range of transitional justice measures are prioritized in the set of responses available to the Security Council’s Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict. ICTJ maintains that transitional justice measures can contribute to efforts to reveal the underlying causes of violations against children, remedy the consequences and prevent their recurrence.

“We need to understand what drives state and non-state actors to criminal acts such as forcible recruitment of child soldiers in order to fully address them. Truth-seeking can help to do that,” says Tolbert. “Military, security and other state institutions that engage in such practices must be thoroughly reformed if we are to avoid their recurrence. And the harm done to children must be dealt with through carefully devised reparations programs to allay long-term consequences of the suffering inflicted upon them.”

ICTJ will call upon the Security Council to build on the progress made over the past decade and utilize its leverage to support national processes working to address the full range of violations against children.

“The Council should continue to recognize that protection of children

and accountability for grave violations against children are part of

the Council’s role in upholding peace and security,” said Tolbert. “With

this in mind, the Council should urge donors to support national

processes that seek to achieve accountability in a comprehensive

manner.”

In addition, ICTJ will call for increased focus on accountability within Action Plans the UN has entered with parties to conflict where children were targeted. ICTJ believes that the UN Action Plans to address violations against children are a starting point to achieving accountability for violations against children. “It will also be important to see Actions Plans on the other grave violations against children,” says Tolbert.

ICTJ is the only non-governmental organization invited to address the UN Security Council’s annual open debate on children in armed conflict this year. The debate will be held on September 19, 2012, at 10:00 am United Nations headquarters in New York. The session may be viewed live on the UN’s streaming channel, at webtv.un.org. The full text of ICTJ’s address will be made available immediately after the address at www.ictj.org.

Source: http://ictj.org/news/ictj-brief-un-security-council-accountability-crimes-against-children

“Prosecutions are essential for accountability, as they send a clear message that certain violations will not be tolerated by the society or the international community. However, ICTJ’s work over the past decade in over 40 countries has shown that in isolation, prosecutions are not enough,” said David Tolbert, president of ICTJ.

In his address to the Security Council, Tolbert will recommend that the full range of transitional justice measures are prioritized in the set of responses available to the Security Council’s Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict. ICTJ maintains that transitional justice measures can contribute to efforts to reveal the underlying causes of violations against children, remedy the consequences and prevent their recurrence.

“We need to understand what drives state and non-state actors to criminal acts such as forcible recruitment of child soldiers in order to fully address them. Truth-seeking can help to do that,” says Tolbert. “Military, security and other state institutions that engage in such practices must be thoroughly reformed if we are to avoid their recurrence. And the harm done to children must be dealt with through carefully devised reparations programs to allay long-term consequences of the suffering inflicted upon them.”

ICTJ will call upon the Security Council to build on the progress made over the past decade and utilize its leverage to support national processes working to address the full range of violations against children.

|

| Photo: Pierre Holtz | UNICEF CAR |

In addition, ICTJ will call for increased focus on accountability within Action Plans the UN has entered with parties to conflict where children were targeted. ICTJ believes that the UN Action Plans to address violations against children are a starting point to achieving accountability for violations against children. “It will also be important to see Actions Plans on the other grave violations against children,” says Tolbert.

ICTJ is the only non-governmental organization invited to address the UN Security Council’s annual open debate on children in armed conflict this year. The debate will be held on September 19, 2012, at 10:00 am United Nations headquarters in New York. The session may be viewed live on the UN’s streaming channel, at webtv.un.org. The full text of ICTJ’s address will be made available immediately after the address at www.ictj.org.

Source: http://ictj.org/news/ictj-brief-un-security-council-accountability-crimes-against-children

Monday 17 September 2012

Forced Disappearances Are Crimes Against Humanity That Can't Be Justified

9/4/2012

By Paul Seils, vice president of the International Center for Transitional Justice

On September 12, 1981, in downtown Tegucigalpa, Manfredo Velasquez was abducted in broad daylight by heavily armed men dressed in civilian clothes driving a white Ford without license plates. He was never seen again.

Manfredo was a student whose “activities” in a national student union were deemed by the Honduran junta to be dangerous for “national security.” The precise fate of Manfredo will never be known, but witnesses testified that he was almost certainly tortured and then killed by the security forces that took him. Seven years later, in a historic first judgment, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights found the government of Honduras responsible for Velasquez’ disappearance. However, forced disappearance continues as a state-sanctioned practice in many countries even today.

And it is not only the dictatorships of Latin America that were in thrall to the “benefits” of such approaches. The response of Assad’s regime to calls for reform and democracy in Syria included multiple incidents of forced disappearance. Systematic long-term detention practiced under Mubarak in Egypt, Ben Ali in Tunisia and Gaddafi in Libya are also examples. Behind by the grandiose, Orwellian disguise of “extraordinary rendition,” the United States and many of its allies have been engaged in executing or colluding in a practice that is nothing other than forced disappearance.

The reason, it seems clear, for the practice of “extraordinary renditions” is to allow those disappeared to be subjected to treatment that would be plainly illegal in the US. Morally it is indefensible. Strategically it is nonsensical: what could be more self-defeating in a battle to defend values than to subvert them so completely in the face of attack. While the Obama administration has taken steps to limit the practice, some forms of it continue and there has been no attempt to reckon with past practices.

It is possible for all sorts of people to carry out forced disappearances, but our concern should be first and foremost with state actors. It is hard to imagine a more cowardly or terrifying abuse of state power than to subvert the most fundamental rights of an individual by disappearing them. Make no mistake – disappearance is a terror tactic – a tactic of terrorism. The means of its execution may become more sophisticated, but the fact that a state is behind it should make it more, not less reprehensible.

The aims of disappearance as a tactic are multiple: it rids the state of opponents, real or imagined; it says “you are nothing, your identity is nothing, your existence is nothing”, it inflicts massive cruelty on those disappeared to provide an extra layer of terror to those left behind; it leaves loved ones burdened for life, condemned to a twilight of fear-filled unknowing. It is hard to think of any carefully planned practice that could so perfectly encapsulate the capacity for human beings in power to debase themselves and dehumanize their victims.

From the day Manfredo Velazquez was taken his family tried to find out where he was but the legal system in his country made a mockery of his and his family’s rights. They could find out nothing.

The decision of the Inter American Court on Human Rights in the seminal “Velazquez Rodriguez” case, seven year’s after Manfredo was disappeared is, arguably, one of the most important court decisions on human rights. It established important standards on what State authorities had to do to make sure the practice of forced disappearances were stopped and in what states had to do to remedy any such violations.

At the heart of those remedies was the identification of the right to truth – that a victim or the victim’s relatives had a right to know what had happened and why; a right to justice – that those responsible for the violations and especially the organization systematic practice of forced disappearance should face justice; and that meaningful reparations should be made to the victims. Manfredo’s case, in many ways, is the first court case to set out the legal ideas that marked the birth of what we today know as transitional justice – the ways in which the rights of victims should be addressed in the wake of massive violations.

While the practice of forced disappearance as a state tactic has a long history, it came under the spotlight during the 1980’s when Argentina and then the Inter-American Human Rights system began to hold those responsible to account. August 30 has been recognized as the UN International Day of the Disappeared. One of the most significant developments in human rights protection of recent times was the International Convention for the Protection of all Persons from Enforced Disappearance which entered into force on 23 December 2010.

These are concrete manifestations of important developments, highlighting which, we hope, will help lead to the eradication of the practice.

The primary message of today must be that it has to stop. That such a practice is not acceptable, under any circumstances. But that is not enough. The legacies of disappearances need to be addressed – the families of the disappeared must have access to the facts – where were their loved ones taken, what happened and why; and those responsible must be held to account. Nothing can encourage such inhumanity so much as impunity.

Manfredo Velazquez never appeared after his Honduran captors abducted him, and it may be cold comfort to his loved ones that his case was a seminal moment in the protection of dissident voices –however palatable or reprehensible their views- around the globe. It is harder now than it was in the past for states to abuse the trust of power so grotesquely. Forced disappearance is a crime against humanity. The decisions made by politicians and officials authorizing such practices in different countries cannot be justified legally or morally. They must be held to account and be shown for what they are: enemies of a civilized society.

Source: http://ictj.org/news/forced-disappearances-are-crimes-against-humanity-can%E2%80%99t-be-justified

|

| A young man stands by graffiti depicting people disappeared during the 1960-96 civil war, during the celebration of the Army Day, in Guatemala City, on June 30, 2011. AFP PHOTO/Johan ORDONEZ |

On September 12, 1981, in downtown Tegucigalpa, Manfredo Velasquez was abducted in broad daylight by heavily armed men dressed in civilian clothes driving a white Ford without license plates. He was never seen again.

Manfredo was a student whose “activities” in a national student union were deemed by the Honduran junta to be dangerous for “national security.” The precise fate of Manfredo will never be known, but witnesses testified that he was almost certainly tortured and then killed by the security forces that took him. Seven years later, in a historic first judgment, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights found the government of Honduras responsible for Velasquez’ disappearance. However, forced disappearance continues as a state-sanctioned practice in many countries even today.

And it is not only the dictatorships of Latin America that were in thrall to the “benefits” of such approaches. The response of Assad’s regime to calls for reform and democracy in Syria included multiple incidents of forced disappearance. Systematic long-term detention practiced under Mubarak in Egypt, Ben Ali in Tunisia and Gaddafi in Libya are also examples. Behind by the grandiose, Orwellian disguise of “extraordinary rendition,” the United States and many of its allies have been engaged in executing or colluding in a practice that is nothing other than forced disappearance.

The reason, it seems clear, for the practice of “extraordinary renditions” is to allow those disappeared to be subjected to treatment that would be plainly illegal in the US. Morally it is indefensible. Strategically it is nonsensical: what could be more self-defeating in a battle to defend values than to subvert them so completely in the face of attack. While the Obama administration has taken steps to limit the practice, some forms of it continue and there has been no attempt to reckon with past practices.

It is possible for all sorts of people to carry out forced disappearances, but our concern should be first and foremost with state actors. It is hard to imagine a more cowardly or terrifying abuse of state power than to subvert the most fundamental rights of an individual by disappearing them. Make no mistake – disappearance is a terror tactic – a tactic of terrorism. The means of its execution may become more sophisticated, but the fact that a state is behind it should make it more, not less reprehensible.

The aims of disappearance as a tactic are multiple: it rids the state of opponents, real or imagined; it says “you are nothing, your identity is nothing, your existence is nothing”, it inflicts massive cruelty on those disappeared to provide an extra layer of terror to those left behind; it leaves loved ones burdened for life, condemned to a twilight of fear-filled unknowing. It is hard to think of any carefully planned practice that could so perfectly encapsulate the capacity for human beings in power to debase themselves and dehumanize their victims.

From the day Manfredo Velazquez was taken his family tried to find out where he was but the legal system in his country made a mockery of his and his family’s rights. They could find out nothing.

The decision of the Inter American Court on Human Rights in the seminal “Velazquez Rodriguez” case, seven year’s after Manfredo was disappeared is, arguably, one of the most important court decisions on human rights. It established important standards on what State authorities had to do to make sure the practice of forced disappearances were stopped and in what states had to do to remedy any such violations.

At the heart of those remedies was the identification of the right to truth – that a victim or the victim’s relatives had a right to know what had happened and why; a right to justice – that those responsible for the violations and especially the organization systematic practice of forced disappearance should face justice; and that meaningful reparations should be made to the victims. Manfredo’s case, in many ways, is the first court case to set out the legal ideas that marked the birth of what we today know as transitional justice – the ways in which the rights of victims should be addressed in the wake of massive violations.

While the practice of forced disappearance as a state tactic has a long history, it came under the spotlight during the 1980’s when Argentina and then the Inter-American Human Rights system began to hold those responsible to account. August 30 has been recognized as the UN International Day of the Disappeared. One of the most significant developments in human rights protection of recent times was the International Convention for the Protection of all Persons from Enforced Disappearance which entered into force on 23 December 2010.

These are concrete manifestations of important developments, highlighting which, we hope, will help lead to the eradication of the practice.

The primary message of today must be that it has to stop. That such a practice is not acceptable, under any circumstances. But that is not enough. The legacies of disappearances need to be addressed – the families of the disappeared must have access to the facts – where were their loved ones taken, what happened and why; and those responsible must be held to account. Nothing can encourage such inhumanity so much as impunity.

Manfredo Velazquez never appeared after his Honduran captors abducted him, and it may be cold comfort to his loved ones that his case was a seminal moment in the protection of dissident voices –however palatable or reprehensible their views- around the globe. It is harder now than it was in the past for states to abuse the trust of power so grotesquely. Forced disappearance is a crime against humanity. The decisions made by politicians and officials authorizing such practices in different countries cannot be justified legally or morally. They must be held to account and be shown for what they are: enemies of a civilized society.

Source: http://ictj.org/news/forced-disappearances-are-crimes-against-humanity-can%E2%80%99t-be-justified

Thursday 13 September 2012

Friday 20 April 2012

Wednesday 11 April 2012

Kenya: New Justice Effort Meets Scepticism

Judie Kaberia

4 April, 2012

Institute for War & Peace Reporting (London)

Judie Kaberia is an IWPR-trained reporter in Nairobi.

Rights groups in Kenya are questioning whether a new taskforce set up

by the Director of Public Prosecutions, DPP, to review criminal cases

stemming from post-election violence in 2007 and 2008 will deliver

justice.

They are concerned that the multi-agency taskforce could serve as a smokescreen for continuing inaction. Even if they are proved wrong, it is unclear whether the force will be able to ensure allegations against Kenyan police are properly dealt with.

Months of violence following a disputed presidential election in December 2007 left 1,333 people dead and 350,000 displaced. According to a December 2011 report by the advocacy group Human Rights Watch, only six cases have so far resulted in convictions in the Kenyan courts.

The 20-member taskforce was established on February 9 with a mandate to assess the progress of current investigations into the post-election violence, and to decide whether there is enough evidence to pursue 5,000 cases that are currently before the courts.

The panel, drawn from the DPP's office, the police, justice ministry, the attorney general's office and the witness protection agency, will make recommendations on what actions the government should take to bring the alleged perpetrators of the violence to justice. Dorcas Oduor, a top prosecution official who is heading the taskforce, pledged to submit a report with the recommendations before Kenya's next presidential election, scheduled for March 2013.

It is not the first time the Kenyan authorities have pledged to prosecute the perpetrators of violence. But so far its commitments have not translated into action.

The government twice submitted a bill that would have established a national tribunal to try election violence cases, but parliament rejected it on both occasions.

After the government repeatedly failed to launch domestic prosecutions, the International Criminal Court, ICC, launched its own investigations in March 2010.

The fact that this international intervention was necessary at all raises questions about the Kenyan state's willingness to ensure that justice is served. The announcement of the DPP taskforce came just two weeks after the ICC confirmed charges against four of the six suspects that the tribunal's prosecutor investigated.

In January 2012, ICC judges confirmed that Kenya's deputy prime minister, Uhuru Kenyatta, former higher education minister William Ruto, cabinet secretary, Francis Muthaura, and Kass FM radio presenter Joshua Arap Sang would face trial for crimes against humanity, as alleged orchestrators of the violence.

"It is interesting that the government is talking again about bringing accountability to the victims. This is the third time that the DPP has put together a team to investigate the 5,000 cases, but nothing [has yet] happened," Neela Ghoshal, Nairobi-based researcher for Human Rights Watch, said.

"Sometimes the justice system can function independently. But the big question is how many Kenyans trust the local courts? Any time there is something happening at the ICC, the government makes many statements on how it's going to seek justice in Kenya."

On past record, Ghoshal has yet to be convinced that the new taskforce will pave way for prosecutions of lower- and mid-level perpetrators.

"What different is this taskforce going to make?" she said. "There are thousands of cases out there. One cannot really trust such statements from the government until we see the results. There are other areas in which the government - if it cared about the victims - could have made a difference yesterday."

According to the Commission of Inquiry on Post Election Violence, an international investigative panel set up by the Kenyan government, police were responsible for at least 405 fatal shootings and hundreds of injuries and rapes during the disturbances of 2007-08.

In its investigations into the actions of top-level figures accused of sponsoring the violence, the ICC found reasonable grounds to believe that police were deployed in strongholds of the coalition government's Orange Democratic Movement, including Kisumu, and used excessive force against civilians.

Despite this, no member of the police force has been convicted. One police officer was prosecuted in relation to police shootings in Kisumu, but he was later released.

The Kenyan government insists investigations into the Kisumu shootings are continuing. But the DPP has not said how many of the 5,000 post-election violence cases currently before the courts involve allegations against the police.

Christine Alai of the International Centre for Transitional Justice, ICTJ, in Nairobi warned that the taskforce must not conduct substandard investigations into the actions of police, or omit important cases.

"It is obvious something has to be done with police... to ensure we can get accountability and that cases are not thrown out on technicalities. The process should not be a sham due to shoddy investigations. Victims and Kenyans are tired of sham processes," Alai warned, referring to previous investigations into the shootings in Kisumu.

Ghoshal says Kenyan police have repeatedly failed to admit responsibility for crimes against civilians. According to victims interviewed by Human Rights Watch, police failed to document complaints submitted during the violence.

"I have spoken to victims who were shot by police. They told me they went to the police and told them that they had been shot by the police. And a number of police said to them, "Sorry we can't [accept] that," said Ghoshal.

Ghoshal contrasted the authorities' failure to bring criminal prosecutions with the civil cases which a number of victims of the violence have successfully brought against police force members.

"Twenty victims have won the civil cases [against the police] and the majority of them in Kisumu and Nairobi, yet the attorney general has refused to pay damages, so where is the political will of the government?" Ghoshal said.

Ken Wafula, director of the Eldoret-based Centre for Human Rights and Democracy, doubts whether police will be investigated and prosecuted. He would like to see a local tribunal drawn from international as well as Kenyan legal experts.

"There are challenges. How do you grill the police who are supposed to carry out the investigations? Some of them are perpetrators. That is why we have been asking for a special tribunal. It would have been the most appropriate mechanism to address this matter," he said.

It is not yet clear whether the panel will be able to call for such a special tribunal to be set up to handle outstanding cases, if it deems that appropriate.

Kenya's former justice minister, Mutula Kilonzo, who is now in charge of education, acknowledges that it has been a challenge to prosecute police accused of committing crimes during the unrest.

Kilonzo spoke to IWPR shortly before he was replaced as justice minister on March 27 by Eugene Wamalwa of the coalition government's Party of National Unity.

"Let's appreciate that reforms in the police force are ongoing. The mere fact that crimes were committed by police does not in the end mean that crimes will be covered [up]," he said. "There is also a difference between regular police and the Criminal Investigation Department. I am confident that it is possible to prosecute even police involved in the [post-election] crimes."

Citing a shortage of prosecutors and a lack of funding, Kilonzo warned that the DPP might still struggle to conduct effective prosecutions

"The challenge is that DPP only [exists as a] structure. It is not well funded. It does not have sufficient capacity [and] it has only 93 prosecutors and very little money," he said.

Kilonzo also expressed concern that politicians might interfere with the justice process since some of them view any process designed to uncover the truth about the post-election violence as directed against them.

"Politicians should stop politicising and stop thinking it's about them. They assume the taskforce is about them. The fact is that international crimes occurred in Kenya," he said. "These things happened and will affect the country in future if this is not resolved."

There have been mixed reactions to the DPP's move to make progress on outstanding cases.

Mzalendo Kibunjia, the chairman of the National Cohesion and Integration Commission, NCIC, says the review of the cases comes too late, as Kenyans are now starting to move on from the horrors of 2008.

"I think this is going to open the wounds. The government did not do anything for all these years - people have now begun to heal. This is going to worsen the problem," he said.

By contrast, Wafula believes that reexamining the cases and moving ahead with prosecutions is a necessary evil in order to unearth the truth about the violence and thereby help prevent a repetition of it, particularly around next year's elections.

"It is late, yes; but it is necessary to set an example to Kenyans as they go to the polls. A form of prosecution is good so that people cannot repeat the same [crimes]," he said.

Wafula believes it would make sense to reduce the 5,000 cases to about 300. He argues that this would allow the DPP to deliver exemplary justice while also processing a more manageable number of cases and ensuring the necessary witnesses and solid evidence are in place.

"Let them sieve through the 5,000 cases and thin down to a few cases with evidence. Then deal with perpetrators, to send a message," Wafula said.

Alai of the ICTJ, however, wants as many cases as possible to be investigated thoroughly and objectively.

"It's not a numerical issue," she said, adding that the reasons for past delays in the justice process should also be exposed.

"We have to know what happened for the past four years. Why did the process stall?" she said.

Alai hopes that the DPP's initiative is not an attempt to cement the Kenyan government's challenge of admissibility at the ICC. Last August, ICC judges rejected a challenge to the legality of the court's intervention in Kenya.

Following the confirmation of charges against four suspects this January, lawyers lodged a second admissibility challenge based on the view that the alleged crimes were not serious enough to fall under the ICC's jurisdiction. The court's appeal judges are currently considering this submission.

"Let [the government] not focus on ICC, let the process take its course," Alai said.

Source: http://allafrica.com/stories/201204041065.html

4 April, 2012

Institute for War & Peace Reporting (London)

Judie Kaberia is an IWPR-trained reporter in Nairobi.

|

| Kenyan's queue on 27 December 2007 to cast their vote in the country's General Election. Opinion polls put the presidential election as the closest since Kenya's independence in 1963. |

They are concerned that the multi-agency taskforce could serve as a smokescreen for continuing inaction. Even if they are proved wrong, it is unclear whether the force will be able to ensure allegations against Kenyan police are properly dealt with.

Months of violence following a disputed presidential election in December 2007 left 1,333 people dead and 350,000 displaced. According to a December 2011 report by the advocacy group Human Rights Watch, only six cases have so far resulted in convictions in the Kenyan courts.

The 20-member taskforce was established on February 9 with a mandate to assess the progress of current investigations into the post-election violence, and to decide whether there is enough evidence to pursue 5,000 cases that are currently before the courts.

The panel, drawn from the DPP's office, the police, justice ministry, the attorney general's office and the witness protection agency, will make recommendations on what actions the government should take to bring the alleged perpetrators of the violence to justice. Dorcas Oduor, a top prosecution official who is heading the taskforce, pledged to submit a report with the recommendations before Kenya's next presidential election, scheduled for March 2013.

It is not the first time the Kenyan authorities have pledged to prosecute the perpetrators of violence. But so far its commitments have not translated into action.

The government twice submitted a bill that would have established a national tribunal to try election violence cases, but parliament rejected it on both occasions.

After the government repeatedly failed to launch domestic prosecutions, the International Criminal Court, ICC, launched its own investigations in March 2010.

The fact that this international intervention was necessary at all raises questions about the Kenyan state's willingness to ensure that justice is served. The announcement of the DPP taskforce came just two weeks after the ICC confirmed charges against four of the six suspects that the tribunal's prosecutor investigated.

In January 2012, ICC judges confirmed that Kenya's deputy prime minister, Uhuru Kenyatta, former higher education minister William Ruto, cabinet secretary, Francis Muthaura, and Kass FM radio presenter Joshua Arap Sang would face trial for crimes against humanity, as alleged orchestrators of the violence.

"It is interesting that the government is talking again about bringing accountability to the victims. This is the third time that the DPP has put together a team to investigate the 5,000 cases, but nothing [has yet] happened," Neela Ghoshal, Nairobi-based researcher for Human Rights Watch, said.

"Sometimes the justice system can function independently. But the big question is how many Kenyans trust the local courts? Any time there is something happening at the ICC, the government makes many statements on how it's going to seek justice in Kenya."

On past record, Ghoshal has yet to be convinced that the new taskforce will pave way for prosecutions of lower- and mid-level perpetrators.

"What different is this taskforce going to make?" she said. "There are thousands of cases out there. One cannot really trust such statements from the government until we see the results. There are other areas in which the government - if it cared about the victims - could have made a difference yesterday."

|

| Opposition supporters brandish crude weapons during protests in Nairobi December 31, 2007. |

FAILURE TO ADDRESS POLICE ROLE IN VIOLENCE

According to the Commission of Inquiry on Post Election Violence, an international investigative panel set up by the Kenyan government, police were responsible for at least 405 fatal shootings and hundreds of injuries and rapes during the disturbances of 2007-08.

In its investigations into the actions of top-level figures accused of sponsoring the violence, the ICC found reasonable grounds to believe that police were deployed in strongholds of the coalition government's Orange Democratic Movement, including Kisumu, and used excessive force against civilians.

Despite this, no member of the police force has been convicted. One police officer was prosecuted in relation to police shootings in Kisumu, but he was later released.

The Kenyan government insists investigations into the Kisumu shootings are continuing. But the DPP has not said how many of the 5,000 post-election violence cases currently before the courts involve allegations against the police.

Christine Alai of the International Centre for Transitional Justice, ICTJ, in Nairobi warned that the taskforce must not conduct substandard investigations into the actions of police, or omit important cases.

"It is obvious something has to be done with police... to ensure we can get accountability and that cases are not thrown out on technicalities. The process should not be a sham due to shoddy investigations. Victims and Kenyans are tired of sham processes," Alai warned, referring to previous investigations into the shootings in Kisumu.

Ghoshal says Kenyan police have repeatedly failed to admit responsibility for crimes against civilians. According to victims interviewed by Human Rights Watch, police failed to document complaints submitted during the violence.

"I have spoken to victims who were shot by police. They told me they went to the police and told them that they had been shot by the police. And a number of police said to them, "Sorry we can't [accept] that," said Ghoshal.

Ghoshal contrasted the authorities' failure to bring criminal prosecutions with the civil cases which a number of victims of the violence have successfully brought against police force members.

"Twenty victims have won the civil cases [against the police] and the majority of them in Kisumu and Nairobi, yet the attorney general has refused to pay damages, so where is the political will of the government?" Ghoshal said.

Ken Wafula, director of the Eldoret-based Centre for Human Rights and Democracy, doubts whether police will be investigated and prosecuted. He would like to see a local tribunal drawn from international as well as Kenyan legal experts.

"There are challenges. How do you grill the police who are supposed to carry out the investigations? Some of them are perpetrators. That is why we have been asking for a special tribunal. It would have been the most appropriate mechanism to address this matter," he said.

It is not yet clear whether the panel will be able to call for such a special tribunal to be set up to handle outstanding cases, if it deems that appropriate.

|

| Prime Minister of Kenya, Raila Odinga. |

ARE AUTHORITIES WILLING OR ABLE TO PURSUE CASES?

Kenya's former justice minister, Mutula Kilonzo, who is now in charge of education, acknowledges that it has been a challenge to prosecute police accused of committing crimes during the unrest.

Kilonzo spoke to IWPR shortly before he was replaced as justice minister on March 27 by Eugene Wamalwa of the coalition government's Party of National Unity.

"Let's appreciate that reforms in the police force are ongoing. The mere fact that crimes were committed by police does not in the end mean that crimes will be covered [up]," he said. "There is also a difference between regular police and the Criminal Investigation Department. I am confident that it is possible to prosecute even police involved in the [post-election] crimes."

Citing a shortage of prosecutors and a lack of funding, Kilonzo warned that the DPP might still struggle to conduct effective prosecutions

"The challenge is that DPP only [exists as a] structure. It is not well funded. It does not have sufficient capacity [and] it has only 93 prosecutors and very little money," he said.

Kilonzo also expressed concern that politicians might interfere with the justice process since some of them view any process designed to uncover the truth about the post-election violence as directed against them.

"Politicians should stop politicising and stop thinking it's about them. They assume the taskforce is about them. The fact is that international crimes occurred in Kenya," he said. "These things happened and will affect the country in future if this is not resolved."

There have been mixed reactions to the DPP's move to make progress on outstanding cases.

Mzalendo Kibunjia, the chairman of the National Cohesion and Integration Commission, NCIC, says the review of the cases comes too late, as Kenyans are now starting to move on from the horrors of 2008.

"I think this is going to open the wounds. The government did not do anything for all these years - people have now begun to heal. This is going to worsen the problem," he said.

By contrast, Wafula believes that reexamining the cases and moving ahead with prosecutions is a necessary evil in order to unearth the truth about the violence and thereby help prevent a repetition of it, particularly around next year's elections.

"It is late, yes; but it is necessary to set an example to Kenyans as they go to the polls. A form of prosecution is good so that people cannot repeat the same [crimes]," he said.

Wafula believes it would make sense to reduce the 5,000 cases to about 300. He argues that this would allow the DPP to deliver exemplary justice while also processing a more manageable number of cases and ensuring the necessary witnesses and solid evidence are in place.

"Let them sieve through the 5,000 cases and thin down to a few cases with evidence. Then deal with perpetrators, to send a message," Wafula said.

Alai of the ICTJ, however, wants as many cases as possible to be investigated thoroughly and objectively.

"It's not a numerical issue," she said, adding that the reasons for past delays in the justice process should also be exposed.

"We have to know what happened for the past four years. Why did the process stall?" she said.

Alai hopes that the DPP's initiative is not an attempt to cement the Kenyan government's challenge of admissibility at the ICC. Last August, ICC judges rejected a challenge to the legality of the court's intervention in Kenya.

Following the confirmation of charges against four suspects this January, lawyers lodged a second admissibility challenge based on the view that the alleged crimes were not serious enough to fall under the ICC's jurisdiction. The court's appeal judges are currently considering this submission.

"Let [the government] not focus on ICC, let the process take its course," Alai said.

Source: http://allafrica.com/stories/201204041065.html

Wednesday 4 April 2012

Guatemala becomes the 121st State to join the ICC’s Rome Statute system

Press Release: 03.04.2012

ICC-CPI-20120403-PR783

|

| Guatemala deposits its instrument of accession to the Rome Statute of the ICC at the United Nations Headquarters in New York on 2 April 2012 © UN/Win Khine |

On 2 April 2012, the United Nations received from the

Government of the Republic of Guatemala its instrument of accession to

the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC). The Rome

Statute will enter into force for Guatemala on 1 July 2012, bringing to

121 the total number of States Parties.

The ICC welcomed Guatemala's accession to the Rome

Statute. The ICC President, Judge Sang-Hyun Song, stated: “I am

delighted that the statements made by Guatemala at the Review Conference

of 2010 as well as the latest Assembly of States Parties concerning its

intention to join the ICC have now fully materialised. With the

historic step now taken by Guatemala, only two countries in Central

America – El Salvador and Nicaragua – remain outside the Rome Statute

system, and I hope they too will actively consider acceding to the

treaty in the near future”.

The President of the Assembly of States Parties, Ms

Tiina Intelmann, commented: “The accession by Guatemala is a testament

to the will and steadfast determination of its people and its leaders to

strengthen the rule of law and to contribute to the international

endeavour to end impunity for egregious crimes”.

Source: http://www.icc-cpi.int/NR/exeres/E2BBA18C-A830-4504-B9BE-6F118C3690F7.htm

Friday 30 March 2012

Building the First Line of Defense against Impunity: Podcast with Phakiso Mochochoko

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST HERE

Earlier this month the International Criminal Court (ICC) handed down its first verdict, finding former rebel leader Thomas Lubanga Dyilo guilty of conscripting and using child soldiers in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

This historic verdict was over three years in the making, and comes just before the court celebrates its 10 year anniversary in July of this year. While this marks a critical milestone in the international justice movement, the court’s critics and supporters alike point out there is much room for improvement, not least in the length of time required for the ICC to deliver justice.

But the ICC is just a component of a larger system of international justice, notes Phakiso Mochochoko, head of the Jurisdiction, Complementarity, and Cooperation Division of the ICC, in ICTJ’s last podcast in our series on complementarity. In fact, “the first line of defense for ending impunity is that of states.”

The Rome Statute "created a system of international justice, with

national judicial systems being at the center of this as the first

bulwark against impunity," he explains. “The ICC is intended to work

with national judicial systems and to intervene only if and when such

national judicial systems are either unwilling or unable generally to

prosecute.”

Under this rubric, he says, a crucial part of the ICC’s mandate is to work with national judicial systems, ensuring they are able to carry out investigations and prosecutions of war crimes and crimes against humanity. We can look to the International Crimes Division of Uganda’s High Court as an example.

“We have worked with the Ugandan authorities, sharing our experiences and information with them and showing them at least how to handle cases of this magnitude. And this has resulted in the war crimes tribunal in Uganda being able to investigate and prosecute one of the criminals in Uganda.”

The global struggle against impunity relies on a frontline of national judicial systems willing and able to prosecute war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. “We have talked enough about complementarity that there are enough people who understand it,” Mochochoko concludes. “It is now time for action.”

Source: http://ictj.org/news/building-first-line-defense-against-impunity-podcast-phakiso-mochochoko

Earlier this month the International Criminal Court (ICC) handed down its first verdict, finding former rebel leader Thomas Lubanga Dyilo guilty of conscripting and using child soldiers in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

This historic verdict was over three years in the making, and comes just before the court celebrates its 10 year anniversary in July of this year. While this marks a critical milestone in the international justice movement, the court’s critics and supporters alike point out there is much room for improvement, not least in the length of time required for the ICC to deliver justice.

But the ICC is just a component of a larger system of international justice, notes Phakiso Mochochoko, head of the Jurisdiction, Complementarity, and Cooperation Division of the ICC, in ICTJ’s last podcast in our series on complementarity. In fact, “the first line of defense for ending impunity is that of states.”

|

| Secretary-General Kofi Annan speaks at the opening ceremony of the signing of the Rome Statute establishing the International Criminal Court, Rome, 18/07/98. UN# 199398C UN/DPI/E/Schneider. |

Under this rubric, he says, a crucial part of the ICC’s mandate is to work with national judicial systems, ensuring they are able to carry out investigations and prosecutions of war crimes and crimes against humanity. We can look to the International Crimes Division of Uganda’s High Court as an example.

“We have worked with the Ugandan authorities, sharing our experiences and information with them and showing them at least how to handle cases of this magnitude. And this has resulted in the war crimes tribunal in Uganda being able to investigate and prosecute one of the criminals in Uganda.”

The global struggle against impunity relies on a frontline of national judicial systems willing and able to prosecute war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. “We have talked enough about complementarity that there are enough people who understand it,” Mochochoko concludes. “It is now time for action.”

Source: http://ictj.org/news/building-first-line-defense-against-impunity-podcast-phakiso-mochochoko

Monday 26 March 2012

Legal Actions against Argentine Officers who Tortured Conscripts during Malvinas War

Monday, March 26, 2012 - 08:15 UTC

MercoPress South Atlantic News Agency

The Buenos Aires Provincial Memory Commission, CMP, will present on Monday an appeal to the Argentine Supreme Court demanding that tortures and other ill treatments suffered by the Argentine conscripts during the Malvinas war by their own officers be considered ‘crimes against humanity’ and therefore imprescriptible.

“The question of the Malvinas war cannot be disassociated from the regime that produced it: the military dictatorship (1976/1983). Nor its illegal methods in the continent from those applied in the Islands”, said the Commission.

The CMP representatives including Nobel Peace laureate Adolfo Perez Esquivel are scheduled to attend at midday Monday the Tribunals Palace in Buenos Aires to make an Amicus Curiae (Friends of the Court) presentation in the case of human rights violations committed by Argentine officers during the Malvinas war.

The initiative supports a recent request from the Criminal Chamber

Prosecutor Javier De Luca who asked the Argentine Supreme Court to rule

if tortures and other abuses denounced by Argentine soldiers against

officers during the war must be considered crimes against humanity of

war crimes.

The presentation includes almost a hundred cases involving Argentine Armed Forces officers, but the investigation was paralyzed once the Annulment Chamber argued that the crimes had prescribed.

Among the claims are cases of staking soldiers to the ground, deaths caused because of lack of food and even killings.

Last week President Cristina Fernandez received the ‘Rattenbach Report” which analyzes the political and military responsibilities of the Malvinas war. Originally elaborated after the conflict by a commission headed by General Benjamin Rattenbach, it was considered too crude and damning towards the commanding officers and then military caretaker president Reynaldo Bignone impeded its release.

Source: http://en.mercopress.com/2012/03/26/legal-actions-against-argentine-officers-who-tortured-conscripts-during-malvinas-war.

MercoPress South Atlantic News Agency

The Buenos Aires Provincial Memory Commission, CMP, will present on Monday an appeal to the Argentine Supreme Court demanding that tortures and other ill treatments suffered by the Argentine conscripts during the Malvinas war by their own officers be considered ‘crimes against humanity’ and therefore imprescriptible.

“The question of the Malvinas war cannot be disassociated from the regime that produced it: the military dictatorship (1976/1983). Nor its illegal methods in the continent from those applied in the Islands”, said the Commission.

The CMP representatives including Nobel Peace laureate Adolfo Perez Esquivel are scheduled to attend at midday Monday the Tribunals Palace in Buenos Aires to make an Amicus Curiae (Friends of the Court) presentation in the case of human rights violations committed by Argentine officers during the Malvinas war.

|

| Nobel Peace laureate Perez Esquivel |

The presentation includes almost a hundred cases involving Argentine Armed Forces officers, but the investigation was paralyzed once the Annulment Chamber argued that the crimes had prescribed.

Among the claims are cases of staking soldiers to the ground, deaths caused because of lack of food and even killings.

Last week President Cristina Fernandez received the ‘Rattenbach Report” which analyzes the political and military responsibilities of the Malvinas war. Originally elaborated after the conflict by a commission headed by General Benjamin Rattenbach, it was considered too crude and damning towards the commanding officers and then military caretaker president Reynaldo Bignone impeded its release.

Source: http://en.mercopress.com/2012/03/26/legal-actions-against-argentine-officers-who-tortured-conscripts-during-malvinas-war.

Thursday 22 March 2012

Sri Lanka Ethnic Groups Divided over UN Resolution

By KRISHAN FRANCIS, Associated Press

Tuesday, March 20, 2012

(03-20) 01:21 PDT COLOMBO, Sri Lanka (AP) --

The Sri Lankan government's campaign to stave off any U.N. call to investigate its wartime conduct is hampering efforts to heal long-simmering ethnic tensions, according to Tamil politicians, rights activists and clergy members.

Nearly three years after the end of a decades-long civil war that pitted the majority Sinhalese government against minority Tamil Tiger rebels seeking an ethnic homeland, the U.N. rights council is expected to vote this week on a resolution urging Sri Lanka to investigate allegations of human rights abuses and seek reconciliation.

The war ended in 2009 with a bloody offensive into Tiger-controlled northern areas by the government of President Mahinda Rajapaksa, a military push that critics say saw thousands of civilians killed as the Tigers were crushed.

But talk of a U.N. resolution calling for a probe and moves toward reconciliation has infuriated Rajapaksa's governments as well as his supporters, who see it as outside interference in Sri Lanka's internal affairs.

In Geneva, where the rights council is based, Sri Lankan diplomats have been quietly urging members of the 47-nation body to defeat the U.S.-backed resolution.

The Catholic church, which has both Tamil and Sinhalese members and which has largely been seen as neutral in the ethnic dispute, has also gotten involved.

The proposed resolution is an "undue meddling in the sovereignty and integrity of Sri Lanka," said a statement from the office of Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith.

The Tigers, a cult-like group known for suicide-bombers and child soldiers, fought for 25 years to create an independent state for Tamils. Despite the bloody end to the war, the government victory was still seen by many as an opportunity for Sri Lanka to rebuild its ethnic relations, which long before the war had been battered by decades of anti-Tamil discrimination by successive Sinhalese-controlled governments.

Many activists suggested quickly resettling people displaced by the war and negotiating Tamil demands for power sharing. Instead, the government is accused of further alienating Tamils by promoting Sinhalese settlements in predominantly Tamil areas, and disregarding all requests to share power.

Now, with the government fighting the proposed U.N. resolution, Tamils say they are being further pushed aside.

Calling the Sri Lankan government "one of the parties of the abuses" at the war's end, a Tamil Catholic bishop and 30 other priests from the country's Tamil north said in a letter to the U.N. rights group that the resolution "could best address concerns of truth-seeking, accountability and reparations for victims in a way that victims, survivors and their families will have confidence. It is only by addressing these that we believe we can move towards genuine reconciliation."

Such talk is widely heard in Sri Lanka's Tamil community.

"Tamils have struggled through peaceful means and through arms, and nothing has succeeded. There is no way there can be another armed insurrection, so the only solution seems to be something that comes through U.N. intervention," said S. Ravichandran, 37, a Tamil taxi driver in Colombo, the capital.

The Tamil National Alliance, the main Tamil political party, calls the resolution a "first and necessary step towards ensuring peace, justice and reconciliation in Sri Lanka."

"The council must ensure that the Sri Lankan government immediately takes steps to offer a political solution to the Tamil people to resolve the long-festering and deep-seated national problem," party leader Rajavarothayam Sampanthan said in a statement.

The government insists, though, that its own investigations were sufficient.

In 2010, the government created a Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission, which gathered evidence on the conflict from both sides. It released its report last December.

While it disputed an earlier U.N. report — which said Sri Lankan troops deliberately targeted civilians — it did recommend that the government give more power to Tamils in areas where they are in the majority. Those recommendations have been ignored by the government.

Now, analysts say the government fears the fallout of another investigation.

Jehan Perera of National Peace Council, a Sri Lankan organization that promotes peace and good governance, said the government is resisting the proposed resolution because it fears "that this could be the thin edge of the wedge that finally ends in war crimes trials of the government leadership."

The proposal's passage appeared to be one step closer Monday when Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh told Parliament that New Delhi was "inclined to vote in favor of the resolution." India wants "a future for the Tamil community in Sri Lanka that is marked by equality, dignity, justice and self-respect," said Singh, who has been under unrelenting pressure from key Tamil political allies to back the resolution.

Source: http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/n/a/2012/03/19/international/i223501D45.DTL#ixzz1pgtrf8k5

The Sri Lankan government's campaign to stave off any U.N. call to investigate its wartime conduct is hampering efforts to heal long-simmering ethnic tensions, according to Tamil politicians, rights activists and clergy members.

Nearly three years after the end of a decades-long civil war that pitted the majority Sinhalese government against minority Tamil Tiger rebels seeking an ethnic homeland, the U.N. rights council is expected to vote this week on a resolution urging Sri Lanka to investigate allegations of human rights abuses and seek reconciliation.

The war ended in 2009 with a bloody offensive into Tiger-controlled northern areas by the government of President Mahinda Rajapaksa, a military push that critics say saw thousands of civilians killed as the Tigers were crushed.

But talk of a U.N. resolution calling for a probe and moves toward reconciliation has infuriated Rajapaksa's governments as well as his supporters, who see it as outside interference in Sri Lanka's internal affairs.

In Geneva, where the rights council is based, Sri Lankan diplomats have been quietly urging members of the 47-nation body to defeat the U.S.-backed resolution.

The Catholic church, which has both Tamil and Sinhalese members and which has largely been seen as neutral in the ethnic dispute, has also gotten involved.

The proposed resolution is an "undue meddling in the sovereignty and integrity of Sri Lanka," said a statement from the office of Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith.

The Tigers, a cult-like group known for suicide-bombers and child soldiers, fought for 25 years to create an independent state for Tamils. Despite the bloody end to the war, the government victory was still seen by many as an opportunity for Sri Lanka to rebuild its ethnic relations, which long before the war had been battered by decades of anti-Tamil discrimination by successive Sinhalese-controlled governments.

Many activists suggested quickly resettling people displaced by the war and negotiating Tamil demands for power sharing. Instead, the government is accused of further alienating Tamils by promoting Sinhalese settlements in predominantly Tamil areas, and disregarding all requests to share power.

Now, with the government fighting the proposed U.N. resolution, Tamils say they are being further pushed aside.

Calling the Sri Lankan government "one of the parties of the abuses" at the war's end, a Tamil Catholic bishop and 30 other priests from the country's Tamil north said in a letter to the U.N. rights group that the resolution "could best address concerns of truth-seeking, accountability and reparations for victims in a way that victims, survivors and their families will have confidence. It is only by addressing these that we believe we can move towards genuine reconciliation."

Such talk is widely heard in Sri Lanka's Tamil community.

"Tamils have struggled through peaceful means and through arms, and nothing has succeeded. There is no way there can be another armed insurrection, so the only solution seems to be something that comes through U.N. intervention," said S. Ravichandran, 37, a Tamil taxi driver in Colombo, the capital.

The Tamil National Alliance, the main Tamil political party, calls the resolution a "first and necessary step towards ensuring peace, justice and reconciliation in Sri Lanka."

"The council must ensure that the Sri Lankan government immediately takes steps to offer a political solution to the Tamil people to resolve the long-festering and deep-seated national problem," party leader Rajavarothayam Sampanthan said in a statement.

The government insists, though, that its own investigations were sufficient.

In 2010, the government created a Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission, which gathered evidence on the conflict from both sides. It released its report last December.

While it disputed an earlier U.N. report — which said Sri Lankan troops deliberately targeted civilians — it did recommend that the government give more power to Tamils in areas where they are in the majority. Those recommendations have been ignored by the government.

Now, analysts say the government fears the fallout of another investigation.

Jehan Perera of National Peace Council, a Sri Lankan organization that promotes peace and good governance, said the government is resisting the proposed resolution because it fears "that this could be the thin edge of the wedge that finally ends in war crimes trials of the government leadership."

The proposal's passage appeared to be one step closer Monday when Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh told Parliament that New Delhi was "inclined to vote in favor of the resolution." India wants "a future for the Tamil community in Sri Lanka that is marked by equality, dignity, justice and self-respect," said Singh, who has been under unrelenting pressure from key Tamil political allies to back the resolution.

Source: http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/n/a/2012/03/19/international/i223501D45.DTL#ixzz1pgtrf8k5

Monday 19 March 2012

Update: Historic Verdict Condemns Warlord, but Hague Court Limited

By Anthony Deutsch

The International Criminal Court convicted the little known militia leader of using child soldiers in the Democratic Republic of Congo. But critics noted that deadlock among world powers means the ICC is not even investigating daily tales of atrocity emanating from the Syria of President Bashar al-Assad.

Another sitting head of state, Sudan's Omar al-Bashir, cocks a snook at a three-year-old arrest warrant. And big states including the United States, Russia and China, none of which accepts the jurisdiction of the Court, trade charges of hypocrisy over their own behavior in places like Iraq, Chechnya or Tibet.

Navi Pillay, a former ICC judge who now heads the U.N. human rights agency, hailed the first verdict in the court's 10-year existence as a "major milestone in the fight against impunity".

But her own agency has been forced to lock away evidence it has gathered against Syrian officials of crimes against humanity during the past year's crackdown on anti-Assad protests, due to the international stalemate in the U.N. Security Council, the only body empowered to order an ICC investigation on Syria.

Many in Congo, and on a continent long ravaged by men like him, welcomed that Lubanga, 51, had been brought to book for snatching boys and girls aged under 15 and forcing them to fight in a five-year jungle war that killed some 60,000 people in the east of the country around the turn of the century.

He will be sentenced only later, and has a month to appeal.

But some Africans grumbled the ICC does too little to hold to account others elsewhere, or is succeeding only in hitting the small fry, or losers like former Ivory Coast president Laurent Gbagbo, who now sits in custody on the Dutch coast.

Watched among others by actress and human rights campaigner Angelina Jolie, Lubanga sat impassively in the dock in white robes and cap, having denied all charges. Yet one of his co-accused still serves as general in the Congolese army - a vivid reminder of the political limitations on the court.

"SHIELDED FROM THE COURT"

It was set up to provide a permanent forum after ad hoc tribunals, inspired by the Nuremberg trials of Nazi leaders, were used to prosecute those responsible for war crimes in the former Yugoslavia and for the Rwandan genocide of the 1990s.

"Two decades ago, international justice was an empty threat," Pillay said. "Since then a great deal has been achieved and the coming of age of the ICC is of immense importance in the struggle to bring justice and deter further crimes."

But the ICC can work only with the assent of political leaders: "Is it going to give pause to Bashar al-Assad?" asked Reed Brody, counsel for Human Rights Watch, of the conviction of a man he called a "small fish" in Africa. "I don't think so."

"Have we seen atrocities fall off in the world? We only have to look at Syria to know it's not the case," he said, noting how veto-wielding Russia and China were blocking Western and Arab efforts to have the Security Council act against Assad.

That is the only way to initiate a prosecution, since Syria, like Russia and China but also the United States, is not a party to the Rome Statute, which created the Court in July 2002. While most countries have signed up, the ICC's big opponents see it as a threat to national sovereignty and to their global interests.

"It's not the fault of the ICC," said Brody, who established a reputation as a scourge of dictators during efforts to try Chile's Augusto Pinochet and Haiti's "Baby Doc" Duvalier. "It's the fault of the Security Council and of the world order ... the international justice system does not operate in a vacuum."

While welcoming the verdict against Lubanga, which may help set a precedent for other cases involving the recruitment of child soldiers, he added: "Those countries with political power and their allies have been shielded from the court."

While there has been talk among international jurists of trying to mount a case against Assad other Syrian officials in the national courts of, for example Spain, Britain or Belgium, which have asserted global jurisdiction for crimes against humanity, there seems little immediate prospect of that.

Assad and his aides also run the risk that defeat could bring prosecution at home, as happened to Saddam Hussein in U.S.-occupied Iraq and faces the son of Muammar Gaddafi, Saif al-Islam, following his capture last year in Libya.

CHILD SOLDIERS

At The Hague on Wednesday, ICC Presiding Judge Adrian Fulford said in reading the court's historic first judgment: "The chamber concludes that the prosecution has proved beyond reasonable doubt that Mr. Thomas Lubanga Dyilo is guilty of conscripting and enlisting children under the age of 15 years."

He was detained six years ago and faced three counts of war crimes. He could face up to life imprisonment. The three-judge panel said children were forced into camps in the Ituri region, where they were placed under harsh training regimes and brutally punished. Soldiers and army commanders under Lubanga's authority used girls as domestic workers and subjected them to rape and sexual violence, they said.

"The accused and his co-perpetrators agreed to, and participated in, a common plan to build an army for the purpose of establishing and maintaining political and military control over Ituri," they said. "This resulted in the conscription and enlistment of boys and girls under the age of 15."

Congolese Justice Minister Luzolo Bambi Lessa hailed the "historic" verdict and said the fact his country has more people facing justice at the ICC than any other showed critics of the Kinshasa government that it was serious about ending abuses.

In the eastern Congolese city of Goma, Sharanjeet Parmar of the human rights group the International Center for Transitional Justice, said: "The result is important for the ICC as Lubanga is its first trial. But more importantly for the DRC in terms of fighting the culture of impunity, because very few people who're accused of war crimes are brought to justice."

Local people, she added, were eager now to see some form of reparation made for their suffering - as well as Bosco Ntaganda, the general indicted along with Lubanga, handed over to the ICC.

"His continued liberty is actually a threat to peace," Parmar said. "It's important that he's handed over in light of the fact he is still implicated in ongoing violations."

AFRICAN SPOTLIGHT

Elsewhere in Africa, there was a welcome for a thug getting his just deserts, but some irritation that others, ranging from Israel and the United States, to Sri Lanka or Syria, had not felt the breath of ICC prosecutors at their heels.

At Bottom Mango Junction in Freetown, capital of Sierra Leone, people with memories of the civil war in their country - for which some are being tried in an internationally-backed local court - praised the ICC's concern for Africans, who have suffered more than most from the depredations of warlords.

"The ICC is treating Africa fairly," said Brian Ansumana, who sells diesel oil. "Because these warlords, they are using children in war, giving them guns, drugs. The ICC is in place to see that those crimes are not committed in Africa."

But in Dakar, capital of Senegal, businessman Papis Fall said: "The court is not fair. We're getting the impression that it focuses solely on African criminals. It should look for criminals everywhere, including America, Europe and ... Israel." George Mukundi of the South Africa-based Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, said of the Lubanga verdict: "What we Africans are saying is, yes, it's useful and good ... But we would also like to see justice done, and being seen to be done, in other cases around the world."

He also voiced concern that the ICC "seems to be looking at only one side of the coin" in targeting some warlords but not other leaders in complex national and regional conflicts.

SYRIAN CONFLICT

The United Nations estimates that some 8,000 Syrians have died in violence since an uprising against Assad began a year ago. Many are civilians and U.N. officials and independent rights groups have amassed evidence from refugees of deliberate killings of demonstrators by Syrian forces and of mass torture.

The United States and its allies have said Assad looks like a war criminal. But political deadlock among the great powers in the Security Council has tied the hands of ICC prosecutors.

"We can't even get a resolution condemning the crackdown, let alone an ICC referral, due to the Russian determination to prevent Council action," one diplomat said in New York.

U.S. State Department spokeswoman Victoria Nuland hailed the Lubanga judgment as "a historic and an important step in providing justice and accountability for the Congolese people".

But she made clear Washington was not about to change its view that the ICC should have no jurisdiction over Americans.

Amnesty International, another group which strongly supports the aims of the court, said: "Today's verdict will give pause to those around the world who commit the horrific crime of using and abusing children both on and off the battlefield."

Source: http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/03/14/us-court-lubanga-idUSBRE82D0J620120314

(Additional reporting by Jonny Hogg in Kinshasa, Simon Akam in Freetown, Pascal Fletcher in Johannesburg and Diadie Ba and Mark John in Dakar, Sara Webb in Amsterdam, Stephanie Nebehay in Geneva and Louis Charbonneau at the United Nations; Editing by Alastair Macdonald and Peter Millership)

THE HAGUE |

Wed Mar 14, 2012 3:06pm EDT

The

war crimes court at The Hague found Congolese warlord Thomas Lubanga

Dyilo guilty on Wednesday in its first ever ruling after a decade of

work limited largely to Africa while major cases elsewhere remain beyond

its reach.The International Criminal Court convicted the little known militia leader of using child soldiers in the Democratic Republic of Congo. But critics noted that deadlock among world powers means the ICC is not even investigating daily tales of atrocity emanating from the Syria of President Bashar al-Assad.

Another sitting head of state, Sudan's Omar al-Bashir, cocks a snook at a three-year-old arrest warrant. And big states including the United States, Russia and China, none of which accepts the jurisdiction of the Court, trade charges of hypocrisy over their own behavior in places like Iraq, Chechnya or Tibet.

Navi Pillay, a former ICC judge who now heads the U.N. human rights agency, hailed the first verdict in the court's 10-year existence as a "major milestone in the fight against impunity".

But her own agency has been forced to lock away evidence it has gathered against Syrian officials of crimes against humanity during the past year's crackdown on anti-Assad protests, due to the international stalemate in the U.N. Security Council, the only body empowered to order an ICC investigation on Syria.

Many in Congo, and on a continent long ravaged by men like him, welcomed that Lubanga, 51, had been brought to book for snatching boys and girls aged under 15 and forcing them to fight in a five-year jungle war that killed some 60,000 people in the east of the country around the turn of the century.

He will be sentenced only later, and has a month to appeal.

But some Africans grumbled the ICC does too little to hold to account others elsewhere, or is succeeding only in hitting the small fry, or losers like former Ivory Coast president Laurent Gbagbo, who now sits in custody on the Dutch coast.

Watched among others by actress and human rights campaigner Angelina Jolie, Lubanga sat impassively in the dock in white robes and cap, having denied all charges. Yet one of his co-accused still serves as general in the Congolese army - a vivid reminder of the political limitations on the court.

|